The north of Jordan offers a fascinating blend of Roman grandeur, Islamic heritage, and stunning natural beauty. North sites tours typically encompass some of the most impressive archaeological parks and historical fortresses, easily accessible as day trips from Amman.

Jerash: The Pompeii of the Middle East Top of the list for any northern Jordan itinerary is Jerash, one of the best-preserved Roman provincial towns in the world. As you step through the monumental Hadrian’s Arch, you’re transported back in time. Wander along the impossibly grand Oval Plaza, imagine gladiators in the Hippodrome, and marvel at the intricate details of the Temple of Artemis. The colonnaded streets, theaters, and churches offer a vivid glimpse into Roman life, making it an incredible historical journey.

Umm Qais (Gadara): Where History Meets Views Perched on a hilltop with unparalleled panoramic views, Umm Qais, ancient Gadara, is truly special. From here, you can gaze across the Sea of Galilee, the Golan Heights, and the Yarmouk River valley – a truly breathtaking sight, especially at sunset. Umm Qais boasts impressive Roman ruins, including two theatres, a basilica, and colonnaded streets. It’s also historically significant as the site where Jesus performed the miracle of the Gadarene swine. The blend of history and stunning vistas makes Umm Qais a unique stop on your North sites tours.

Ajloun Castle: A Mighty Islamic Fortress Just a short drive from Jerash lies Ajloun Castle (Qal’at Ar-Rabad), a 12th-century Islamic fortress built by one of Saladin’s generals to protect trade routes and defend against Crusader invasions. This well-preserved castle offers fantastic views of the surrounding countryside and the Jordan Valley. Exploring its numerous rooms, towers, and hidden passages provides a captivating insight into medieval Islamic military architecture and history.

Jerash is located 48 km north of the capital city of Amman, Located in Jerash Governorate.

Jerash Governorate is one of 12 governorates in Jordan. It is located on the northwestern side of the country. The capital of the governorate is the city of Jerash.

Jerash Governorate has the smallest area of the 12 governorates of Jordan, yet it has the second-highest density in Jordan after Irbid Governorate. Jerash Governorate is ranked 7th by population.

Winter (November through April)

8:00 am – 4:00 pm

Summer

8:00 am – 6:30 pm

April and May

8:00 am – 5:30 pm

The Holy month of Ramadan

8:00 am – 3:30 pm

Amman to Jerash around 60 Minutes.

Jerash To Ajloun Castle around 30 Minutes.

Jerash to Umm Qais around 75 Minutes.

Dead Sea to Jerash Around 90 Minutes.

The Archaeological Museum of Jerash was founded in 1928 inside Jerash Archaeological Site.

The museum contains one exhibition hall in which the artefacts were displayed in a historical sequence from the Neolithic to the Islamic times.

The number of displayed pieces: 600 pieces.

The museum houses large collections of pottery, glass, metals and coins, in addition to precious stones, figurines and statues, stone and marble alters, and mosaics.

In the garden of the museum, Greek and Latin monumental inscriptions are on display next to marble statues and stone sarcophagi.

Jerash (Gerasa) was one of the cities of Decapolis.

It is considered one of the largest Roman provincial cities, with well preserved Roman temples, paved roads, theatres, bridges and baths.

The city also boasts well preserved monumental architectural parts: the Monumental Gate, the Nymphaeum and the Hippodrome.

From the Byzantine period, there are 18 churches, most of which have mosaic floors. The city wall with four gates is still preserved in many places.

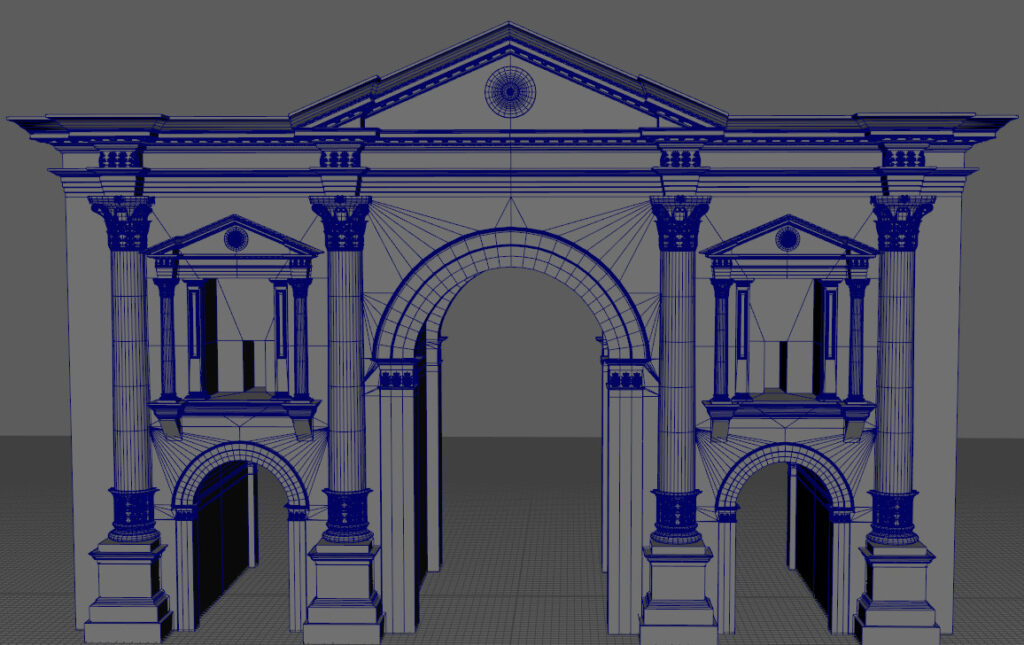

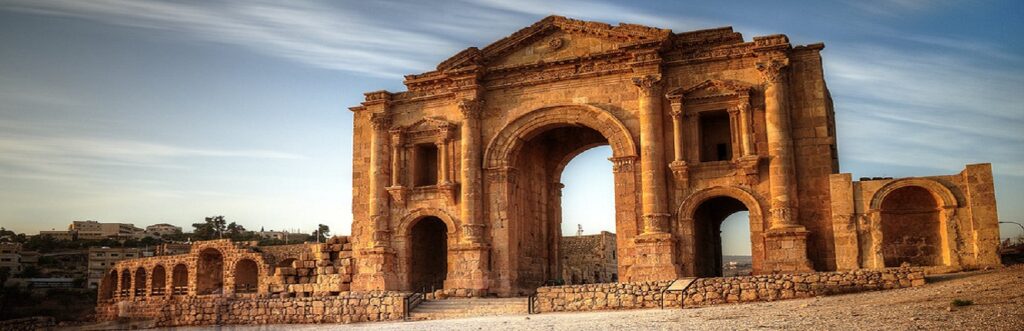

You enter the site of Jerash through this monumental gateway that was constructed to commemorate Emperor Hadrian’s visit in AD 129.

As you pass under the arch, make sure to note the internal decorative carving work. A walkway runs from Hadrian’s Arch for 500 meters to the South Gate where the central set of ruins begin.

Running along the northern side of the walkway is the Jerash Hippodrome, which would have sat 15,000 spectators. Archaeologists have restored and reconstructed much of the Hippodrome, including a section of the tiered seating, allowing visitors to get a feel for how it would have looked originally.

The Arch of Hadrian is an ancient Roman structure in Jerash, Jordan.

It is an 11-metre high triple-arched gateway erected to honour the visit of Roman Emperor Hadrian to the city (then called Gerasa) in the winter of 129–130.

The arch originally stood to almost 22 m and probably had wooden doors.

It features some unconventional, possibly Nabataean, architectural features, such as acanthus bases.

The columns are decorated with capitals at the bottom rather than the top.

The monument served both as a commemorative arch and as an approach to Gerasa.

The Arch’s relative remoteness from the city walls points to a plan for the southward expansion of Gerasa during its heyday.

The expansion, however, has not been implemented.

Once you’ve passed through the South Gate – a smaller version of Hadrian’s Arch – the first set of major ruins is the Sanctuary of Zeus.

The current temple ruins date from AD 162-166, but archaeological excavations here have revealed various other earlier temple remains, including one from the Hellenistic era and an earlier temple dating back to an even earlier settlement period.

Most archaeologists believe that during the Hellenistic era, the town was focused around this temple area.

The temple site is a mass of masonry rubble, which is difficult to decipher, but if you climb to the top of the staircase, to what would have been the temenos (the sanctuary where the God Zeus would have lived), you are rewarded with extensive views looking down on the Oval Plaza below.

A place of worship from the Bronze Age up to the late Roman eras. The sanctuary is made up of two main parts, a lower and an upper terrace. The lower terrace (100 x 50 m) was built first in 27/28 AD by “Diodoros, son of Zebedas, an architect from Gerasa”. A unique feature is a vaulted corridor that ran around the periphery, and which was embellished with facades of Ionic half-columns supporting a Doric frieze. In 162/163 AD, a large temple was built on the higher ground above the sanctuary and a grand staircase was added into the west facade of the lower terrace to access it.

After mid 5th century, the sanctuary was re-used by subsequent settlers as a monastery during Byzantine times and later by farmers and craftsmen. Abandoned after the earthquake of 749 AD, it was briefly reoccupied around the 12th century by a small group of Crusaders.

The Oval Plaza is one of Jerash’s most celebrated features.

It is the only oval-shaped plaza ever found in a Classical-era city site and is incredibly well-preserved. The original paving is still underfoot, and its full package of original Ionic columns have been re-erected, so you are seeing the plaza much as Jerash’s Roman-era residents would have.

At the Oval Plaza’s northeast end is the beginning of the Cardo Maximus, but before you follow that road into the heart of the city ruins, take the trail up the hill to the South Theater from where you can get panoramic vistas of the Oval Plaza from above.

One of the most impressive squares of antiquity. The oval shape is unique and was chosen to harmoniously connect two axes that meet at an angle: the newer one of the Roman Cardo (the long collonaded street) with the axis of the older Sanctuary of Zeus.

The square itself with the Ionic columns was built at the beginning of the 2nd century AD. The paving was done later and was very complex because a 6 to 8 m high substructure had to be built to compensate for a depression.

The spacious plaza measures 90mx80m and is surrounded by a broad sidewalk and colonnade of 1st century AD Ionic columns. There are two altars in the middle, and a fountain was added in the 7th Century AD. This square structure now supports a central column, which was recently erected to carry the Jerash Festival flame.

Jerash has two theatre complexes, but the South Theater is, by far, the most impressive.

Cut half into the hillside, with seating for 3,000 spectators, the South Theater was built at the end of the 1st century.

Due to extensive reconstruction work, as a whole, it is a very striking sight, but visitors should note the well-preserved smaller details on display here, too.

In the seating tiers, look out for Greek letters marking some of the stone slab seats, remnants of the original seat numbering system. Down in the stage area, the backdrop (known as the scaenae frons) has been re-elected, and the masonry is carved with elaborate decoration.

The acoustics from the stage and orchestra areas are exceptional, and you’ll see plenty of fellow visitors testing them out. The best way to experience them, though, is to wait for Jerash’s bagpiper band to troop out into the orchestra area to play a few tunes to demonstrate the acoustics.

This happens regularly throughout the day, whenever enough tourists are in or around the theatre area.

Jordan’s bagpiper tradition dates from the British Mandate period (from the end of World War I to independence in 1946), so the choice of instrument isn’t as random as you may first think.

The South Theater was Built during the reign of Emperor Domitian, between 90-92AD, The first level of the ornate stage, which was originally a two-storey structure, has been reconstructed and is still used today. The theatre’s remarkable acoustics allow a speaker at the centre of the orchestra floor to be heard throughout the entire auditorium without raising his voice. Two vaulted passages lead into the orchestra, and four passages at the back of the theatre give access to the upper rows of seats. Some seats could be reserved and the Greek letters which designate them can still be seen.

The Cardo Maximus is Jerash’s main road, running northeast from the Oval Plaza to the city’s North Gate.

The paving you are walking upon is original, laid out in the 1st Century, when the Romans decided to begin lavishing money on this prosperous trading town and rolled out a city plan of building works, including this grand main thoroughfare.

Keep your eyes peeled to spot the ruts of chariot wheels scored into the stone slabs at various stages along the road.

At various sections, along the road’s length, the original Ionic columns that rim the road have been re-erected.

Along the road section that runs between the Oval Plaza and the South Tetrapylon, you can see the remains of Jerash’s Agora (marketplace). This was discovered by archaeologists in the 1970s, putting to bed the earlier theory that the Oval Plaza had served this role in the city.

A little farther on is the South Tetrapylon, which marks the Cardo’s intersection with the South Decumanus road.

You can follow the South Decumanus up to the remains of an Umayyad-era house before returning and continuing along the Cardo.

Jerash’s superb collonaded cardo Maximus is straight in the way that only a Roman road can be. This is one of Jerash’s great highlights, and the walk along its entire 800m length from North Gate to the forum is well worth the effort. Built-in the 1st century AD and complete with manholes to underground drainage, the street still bears the hallmarks of the city’s principal thoroughfare, with the ruts worn by thousands of chariots scored into the original flagstones.

The 500 columns that once lined the street were deliberately built at different heights to complement the facades of the buildings that stood behind them. Although most of the columns you see today were reassembled in the 1960s, they give an excellent impression of this spectacular thoroughfare.

There are many buildings of interest on either side of the Cardo Maximus, in various states of restoration and ruin. A highlight is the northern tetra pylon, an archway with four entrances.

The first major monument after the South Tetrapylon, along the Cardo Maximus, is the Cathedral Complex, which was built during Jerash’s Byzantine period.

By the early 4th century, Jerash had a significant Christian population, and by the mid-century, the town had become a bishopric. Like many of the churches excavated in Jerash, this site was built atop an earlier Classical-era temple.

From the Cardo, stairs lead up to a courtyard space, known as the Fountain Court, from where you can access the cathedral’s remaining basilica ruins, as well as the separate Church of St. Theodore.

The Church of St. Theodore is the better-preserved church building of the two, and you can easily see the layout of the building with its side aisles and central nave.

Jerash Cathedral was raised on the ruin of the Roman temple to Dionysus, which itself was built on the site of a temple to Dushara, the Nabataean god of the royal house.

The remains of the Roman temple were removed to the level of the podium shortly before the start of construction of the new building of the Cathedral, and its architectural elements, such as columns, were reused as material for the masonry of the church.

Named Cathedral of St. Mary, the ruins are shown in the black and white images which show the entrance to the cathedral compound and the main avenue and the forum.

Further up the Cardo Maximus, on the left is the monumental and richly carved gateway of a 2nd century Roman Temple of Dionysus. In the 4th century, the temple was rebuilt as a Byzantine church now referred to as the ‘Cathedral’ (although there is no evidence that it held more importance than any of the other churches). At the top of the stairs, against an outer East wall of the Cathedral is the shrine of St. Mary, with a painted inscription to Mary and the archangels Michael and Gabriel.

From the Cathedral Complex, it is well worth diverting off the main Cardo Maximus route and taking the rough trail up the hill to view three further church ruins.

The Church of St. George, Church of St. John the Baptist, and Church of SS Cosmas & Damian were all built between AD 529 and 533, and sit in a row sharing an entrance atrium.

The Church of SS Cosmas & Damian is the most interesting, as it contains a vibrant and intricately decorated mosaic floor, which is the best-preserved example of mosaic art excavated in Jerash.

The mosaic is viewed from above (to prevent the floor from being damaged, the church is not open) which allows you an excellent perspective of the floor’s artistry.

The Greek inscription beside the church’s altar dates the mosaic floor to AD 533. The mosaic illustrations depict various animals and portraits, contained in a pattern of diamonds and squares.

Beside the Church of SS Cosmas & Damian, you can enter both the Church of St. George and the Church of St. John the Baptist. Each contains scraps of mosaic decoration.

–

The middle one of a complex of three churches that share an atrium, constructed between 529 and 533 AD. Saint John the Baptist, the largest of the three, is a central church and with four exedras. The central square was formed by four large Corinthian columns which provided the support for the roof over this central area. The nave was covered with a mosaic pavement that praises Bishop Paul and the donor Theodore.

–

As with most other churches in Jerash, this three-aisled basilica was constructed using many stone blocks taken from earlier Roman structures. The main entrance is from the west, consisting of an imposing doorway decorated with intricate carvings and an inscription that says”… It was built in 494/496 during the episcopate of Aeneas and in honour of the victorious Theodore; immortal martyr”.

The Church of St. Theodore is part of a group of buildings on four terraces, rising one above the other on the west side of the Cardo Maximus (main street). The whole group stretches for more than 163 m from east to west, and the buildings on the highest level are more than 18 m above the level of the main street.

–

Discovered in 1983, one of 23 Byzantine churches was found in the ancient city. A mosaic inscription tells that the church was built in 558/559 AD at the time of Bishop Isaiah. As with other buildings of his period in Gerasa, it was built using materials reused from Roman constructions. The church’s three naves are separated by rows of ionic columns, which were probably taken from the North Decumanus. The rich mosaic floor of this church is quite remarkable, with so much of it quite well preserved. Unfortunately, though, the design suffered badly from the iconoclasm of the 8th century when most of the animal and human figures were destroyed.

To the west, an atrium led to the three front entrances. These doors were later blocked and the main entrance transferred to the south side of the church where there was another court with porticoes. The pulpit and chancel, partially preserved at the time of excavation, have not been restored.

This building, like most of the churches in Gerasa, was still in use by a Christian community during the Umayyad period (661 – 750 AD). It seems that, just before the main earthquake that destroyed the city (749 AD), repairs were being made to the walls and the roof of the church.

Jerash’s Nymphaeum is just to the north of the Cathedral Complex, along the Cardo Maximus.

A nymphaeum is a public fountain, found in most Roman city ruins, and Jerash’s one dates from the 2nd century.

It is by far the best-preserved nymphaeum monument in any Classical-era site in Jordan.

Here, you can imagine how impressive the area would have been original, when it was a working public fountain, as the entire two-level back wall of the nymphaeum, with its decorative niches, is still standing.

Originally a domed ceiling would have jutted out from the wall, covering the large basin area below.

As the city of Gerasa thrived and expanded there was a greater need for a substantial and continuous water source within the city. Around 125 AD Gerasa’s water supply system was built, and by the end of the 2nd century, the flow of the main aqueduct was increased to address a growing demand for water following the construction of the baths. This imposing Nymphaeum was then built around 190/191 AD to add a main source of water to the multiple small public fountains that had previously been built along the Cardo.

The Nymphaeum is thus a monumental fountain that served the public’s daily water needs. It sits along the main street and consisted of two side aisles that enclosed a central semi-circular apse that was topped with a concrete vault. The two levels of the facade were richly ornamented with carvings, panels, and Corinthian columns. The lower level was adorned with marble panels and the upper level was decorated with painted stucco. Water spouted from the mouths of several carved lion heads into a large, deep basin that occupied the entire width of the monument. The water would run continuously, and any overflow was collected by the street’s sewage system.

The Sanctuary of Artemis was Jerash’s most important, and largest, temple complex. It dates from Jerash’s heyday era in the mid to late 2nd century.

You can enter the temple complex’s cella (inner temple) using a trail that runs from the Three Churches, but it is much more dramatic and impressive to enter from the monumental staircase beginning at the lowest level along the Cardo Maximus.

Originally, the beginning of the temple entrance would have stretched east of the Cardo Maximus, and if you veer off the road here, you can stand amid the rubble of what was once the propylaeum plaza, which formed part of the temple’s grand entrance.

Cross back onto the Cardo Maximus and begin your ascent up the stairs which, halfway up, leads to an altar terrace. From the altar terrace, the stairway widens into a monumental staircase of three flights, making for a triumphant entranceway.

At the top of the stairs, you can finally see the temple platform with its temenos (the holy of holies where the temple’s god is said to reside) in full. One last flight of stairs leads up to the platform.

The platform is rimmed by 10 towering Corinthian columns. The middle column on the southern side is famous, as it sways slightly.

From the temple platform, you can take the rough trail down the hill to the North Theater or backtrack down the monumental staircase to the Cardo Maximus and continue north from there.

This temple was built as a shrine to Artemis, who was the patron goddess of Gerasa. It lies inside the large courtyard of the sanctuary. Construction of the temple began in the 2nd century AD, however, it was never finished and only 12 columns out of a planned total of 32 were erected.

The temple sits on an extensive system of underground vaults, the exact purpose of which is not known. At the back is an adytum, or an inner shrine, where only the Roman priest would be permitted. It comprises a niche for a deity and two side chambers. One of the chambers has a staircase leading down to the vaults, while the second has a staircase leading up to the roof, indicating that there may have been an altar on top.

The temple was used during later times as well, possibly as a church in the Byzantine era, by potters during Umayyad times and in the 12th century, it may have been used as a fort by a group of Crusaders.

Artemis was the patron goddess of the city and was the Hellenistic interpretation of a local deity likely worshipped before the arrival of the Greek colonists, who instead imported in the city the cult of Zeus Olympios. We have evidence of an older sanctuary of Artemis from few inscriptions. The construction of a new wider sanctuary was started after the Bar Kokhba revolt (AD 136); the propylaeum was completed in AD 150 during the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius, while the temple was never finished.

The portico around the cella was designed with six by eleven columns, of which only eleven columns in the pronaos are still standing, 13.20 m high. The Corinthian capitals are very well preserved and bear the signature of Hygeinos, the contractor in charge of carving the bases, shafts and capitals of the columns. The portico and the cella stand on a podium built by a system of parallel vaults surrounded by a corridor, both accessible by two separate staircases from the cella. Two more staircases lead to the roof of the temple, a flat terrace probably used by the worshippers for rituals.

The interior of the cella was cladded with polychrome marbles, as proven by the clamps’ holes in the walls and fragments of Verde Antico slabs from the floor. At its back is the thalamus, an arched niche hosting the statue of the goddess.

In front of the steps of the temple, 18 m far, the moulded base of the altar has been identified under the structures left by the Byzantine and Early Islamic occupation of the terrace. The altar has a square plan 12 m side and it was built north of the central axis of the temple. From scarce spolia reused in later buildings, it was reconstructed as a tower-like structure with a plain base and half-columns in the upper half.

At the end of the 4th-century, the pagan cults were forbidden by the emperors’ edicts. The temple of Artemis was entirely spoliated of the marble cladding of the cella and the corniche of the gate was dismantled and replaced by plain jambs. The cella was paved with a polychrome mosaic floor and converted into a public reception hall. In the 6th-century the roof of the cella collapsed and the whole building was further transformed into a private residential stronghold in the middle of a wide artisanal quarter that occupied the upper terrace of the sanctuary. The structures of the temple withstood the earthquake in AD 749. Since the early 9th-century, the residence was progressively abandoned and the cella silted up of sandy deposits and garbage dumps. A further earthquake, between the 12th and the 13th-century, demolished the upper half of the walls of the temple and the tumble filled the whole area, inside and around the cella. Nevertheless, the vaults of the podium remained accessible from outside and continued to be frequented until modern times by shepherds, squatters and treasure hunters. There is no evidence that the Temple of Artemis could have been the fort occupied by the Arab garrison mentioned by William of Tyre in AD 1122.

The vaults of the podium were first investigated by W. J. Bankes and C. Barry between 1816 and 1819. The pronaos of the temple and parts of the portico were cleared by Clarence Stanley Fisher and the Anglo-American expedition between 1928 and 1934. The Italian Archaeological Mission works in the sanctuary of Artemis since 1978. In 2018, a cooperative project of conservation was started in the Temple of Artemis by the Jordanian Department of Antiquities and the Italian Archaeological Mission with a grant from the US Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation.

The North Tetrapylon marks the intersection of the streets of the Cardo Maximus with the North Decumanus.

It is in a much better state of preservation than the South Tetrapylon and is a good example of these Roman decorative junction markers.

If you have time, just before you hit the North Tetrapylon veer off the Cardo into the ruins of the West Baths.

Although the remnants here are mostly a jumble of masonry, and difficult to decipher, it’s well worth a visit due to the sheer scale of the complex. The bathhouse here was massive, measuring 75 meters by 50 meters.

From the North Tetrapylon, the Cardo Maximus continues for another 200 meters to the North Gate.

Built ca. 180 AD at the intersection of the Cardo Maximus and the North Decumanus (east-west avenue). Later dedicated to Julia Domna, the second wife of the Roman Emperor Septimius Severus (reigned 193 – 211), and daughter of the Syrian high priest Julius Bassianus. The building, with a more modest design than its southern counterpart, was completely reconstructed in 2001.

This archway with four entrances was built over the intersection of Jerash’s cardo Maximus (the main north-south axis) and the north decumanus (an east-west street). Rebuilt in 2000, it was probably designed as a gateway to the North Theatre.

The elaborate North Tetrapylon is one of two in Jerash. This cube-shaped structure with four arches is the crossroads of the Cardo Maximus (main boulevard) and the east-west avenue called North Decumanus. It was built in 180 AD and later dedicated to Septimius Severus, who was a Roman Emperor from 193 until 211, and his second wife Julia Domna. It is fun to imagine all of the people who have passed through this gate for over 1,800 years.

The North Theatre is explicitly referred to as an odeion in a late 2nd-century inscription that ran along the architrave of the scaenae frons (decorative background of the stage). It was thus used to stage music and poetry recitals.

However, it was originally built as a bouleuterion, used for meetings of the boule (municipal council) and for the assembly of representatives of the 12 civic groups of the city. It had a small cave (seats set in a hemicycle) and a simple scenic wall with three monumental entrances. A section of the seating (cuneus) was reserved for the boule. The three remaining sections were allocated to representatives of each Group in proportion to the importance of the Group, as inscriptions carved on the seats attest. The theatre is the only place in the world found to date where such information on the local civic life of an ancient city is so well preserved.

It is unknown when the bouleuterion was constructed, but it may have been during the reign of Hadrian (117 – 138 AD), or perhaps even Trajan (reigned 98 – 117 AD). It was enlarged and transformed into an odeion in 165/166 AD with the addition of an upper level of seats. It was then equipped with a velum, a removable canvas covering suspended on cables.

The building was eventually abandoned and then reoccupied during the Umayyad era by potters before being reduced to ruins by the earthquake of 749 AD.

From the North Tetrapylon, head west onto the North Decumanus road to reach Jerash’s North Theater.

This area has been painstakingly reconstructed, with a small columned plaza leading into the theatre itself.

The theatre is smaller than the South Theater, and excavations here revealed that the original building, dating from around AD 165, was even smaller still. It was then extended in the 3rd century to sit around 1,500 spectators.

The orchestra area has a colourful marble pavement, though this was completed as part of the reconstruction work in the 1990s.

There are great views over the modern town of Jerash from the top seating tier.

From the North Theater, you can continue west to the 6th-century Church of Bishop Isaiah.

The earliest evidence of settlement in Jerash is in a Neolithic site known as Tal Abu Sowan, where rare human remains dating to around 7500 BC were uncovered.

Jerash flourished during the Greco and Roman periods until the mid-eighth century CE, when the 749 Galilee earthquake destroyed large parts of it, while subsequent earthquakes contributed to additional destruction.

However, in the year 1120, Zahir ad-Din Toghtekin, atabeg of Damascus ordered a garrison of forty men to build up a fort in an unknown site of the ruins of the ancient city, likely the highest spot of the city walls in the north-eastern hills. It was captured in 1121 by Baldwin II, King of Jerusalem, and utterly destroyed. Then, the Crusaders immediately abandoned Jerash and withdrew to Sakib (Seecip); the eastern border of the settlement.

Jerash was then deserted until it reappeared by the beginning of Ottoman rule in the early 16th century.

The census of 1596, had a population of 12 Muslim households. However, archaeologists found a small Mamluk hamlet in the Northwest Quarter which indicates that Jerash was resettled before the Ottoman era.

The excavations conducted since 2011 have shed light on the Middle Islamic period as recent discoveries have uncovered a large concentration of Middle Islamic/Mamluk structures and pottery.

The ancient city has been gradually revealed through a series of excavations that commenced in 1925.

Jerash today is home to one of the best-preserved Greco-Roman cities, which earned it the nickname of “Pompeii of the East”.

Approximately 330,000 visitors arrived in Jerash in 2018, making it one of the most visited sites in Jordan.

The city hosts the Jerash Festival, one of the leading cultural events in the Middle East that attracts tens of thousands of visitors every year.

Neolithic age

Archaeologists have found ruins of settlements dating back to the Neolithic Age. Moreover, in August 2015, an archaeological excavation team from the University of Jordan unearthed two human skulls that date back to the Neolithic period (7500–5500 BC) at a site in Jerash, which forms solid evidence of inhabitance of Jordan in that period especially with the existence of ‘Ain Ghazal Neolithic settlement in Amman. The importance of the discovery lies in the rarity of the skulls, as archaeologists estimate that a maximum of 12 sites across the world contains similar human remains.

Bronze age

Evidence of settlements dating to the Bronze Age (3200 BC – 1200 BC) has been found in the region.

Hellenistic period

Jerash is the site of the ruins of the Greco-Roman city of Gerasa, also referred to as Antioch on the Golden River.

Ancient Greek inscriptions from the city support that the city was founded by Alexander the Great and his general Perdiccas, who allegedly settled aged Macedonian soldiers there during the spring of 331 BC when he left Egypt and crossed Syria en route to Mesopotamia. However, other sources, namely the city’s former name of “Antioch on the Chrysorrhoas, point to a founding by Seleucid King Antioch IV, while still others attribute the founding to Ptolemy II of Egypt.

Roman period

After the Roman conquest in 63 BC, Jerash and the land surrounding it were annexed to the Roman province of Syria, and later joined the Decapolis league of cities. The historian Josephus mentions the city as being principally inhabited by Syrians and also having a small Jewish community.

In AD 106, Jerash was absorbed into the Roman province of Arabia, which included the cities of Philadelphia (modern-day Amman), Petra and Bostra. The Romans ensured security and peace in this area, which enabled its people to devote their efforts and time to economic development and encouraged civic building activity.

Jerash is considered one of the largest and most well-preserved sites of Roman architecture in the world outside Italy. And is sometimes misleadingly referred to as the “Pompeii of the Middle East” or of Asia, referring to its size, extent of excavation and level of preservation.

Jerash was the birthplace of the mathematician Nicomachus of Gerasa (Greek: Νικόμαχος) (c. 60 – c. 120 AD).

In the second half of the 1st century AD, the city of Jerash achieved great prosperity. In AD 106, Emperor Trajan constructed roads throughout the province, and more trade came to Jerash. Emperor Hadrian visited Jerash in AD 129–130. The triumphal arch (or Arch of Hadrian) was built to celebrate his visit.

Byzantine period

The city finally reached a size of about 800,000 square meters within its walls.

Beneath the foundations of a Byzantine church that was built in Jerash in AD 530, there was discovered a mosaic floor with ancient Greek and Hebrew-Aramaic inscriptions. The presence of the Hebrew-Aramaic script has led scholars to think that the place was formerly a synagogue, before being converted into a church.

Jerash was invaded by Persian Sassanids in AD 614. A few years later, the Byzantine army was defeated in the battle of the Yarmouk river by the invading Muslim forces and these territories became part of the Rashidun Caliphate.

Early Muslim period

The city flourished during the Umayyad Caliphate. It had numerous shops and issued coins with the mint named “Jerash” in Arabic. It was also a centre for ceramic manufacture; moulded ceramic lamps had Arabic inscriptions that showed the potter’s name and Jerash as the place of manufacture. The large mosque and several churches that continued to be used as places of worship indicated that during the Umayyad period Jerash had a sizable Muslim community that co-existed with the Christians.

In CE 749, a devastating earthquake destroyed much of Jerash and its surroundings.

Crusader period

In the early 12th century a fortress was built by a garrison stationed in the area by the Zahir ad-Din Toghtekin, atabeg of Damascus. Baldwin II, King of Jerusalem, captured and burned the fortress in 1121–1122 CE. Although the site of the fortification has often been identified with the ruins of the temple of Artemis, there is no evidence of the creation of a fortification in the temple in the 12th century. The location of this fort is probably to be found at the highest point of the city walls, in the north-eastern hills

Mid to Late Muslim period

Small settlements continued in Jerash during the Mamluk Sultanate and Ottoman periods. This occurred particularly in the Northwest Quarter and around the Temple of Zeus, where several Middle Islamic/Mamluk domestic structures have now been excavated.

In 1596, during the Ottoman era, Jerash was noted in the census as Jaras, being located in the nahiya of Bani Ilwan in the Liwa of Ajloun. It had a population of 12 Muslim households. They paid a fixed tax rate of 25% on various agricultural products, including wheat, barley, olive trees/fruit trees, goats and beehives, in addition to occasional revenues and a press for olive oil/grape syrup; a total of 6,000 akçe.

In 1838 Jerash was noted as a ruin.

Archaeology

One of the first to explore the site of Jerash in the 19th century was Prince Abamelek. Excavation and restoration of Jerash have been almost continuous since the 1920s.

Remains in the Greco-Roman Gerasa include

The unique oval plaza, which is surrounded by a fine Ionic colonnade.

The two large sanctuaries were dedicated to Artemis and Zeus with their well-preserved temples.

Two theatres (the South Theatre and the North Theatre).

The long collonaded street or cardo and its side streets or decumani.

The two tetrapyla of Jerash, one at the intersection of northern-decumanus and cardo Maximus and the other at the intersection of southern-Decumanus and cardo Maximus.

The Hadrian’s Arch.

The circus/hippodrome.

Two major thermae (communal baths complexes).

A large nymphaeum is fed by an aqueduct.

A beautiful macellum or porticoed market.

A trapezoidal plaza delimited by two open-exedra buildings.

An almost complete circuit of city walls.

Two large bridges across the nearby river.

An extramural sanctuary with large pools and a small theatre.

Most of these monuments were built by donations from the city’s wealthy citizens. The south theatre has a focus in the centre of the pit in front of the stage, marked by a distinct stone, and from which normal speaking can be heard easily throughout the auditorium. In 2018, at least 14 marble sculptures were discovered in the excavation of the Eastern Baths of Gerasa, including images of Aphrodite and Zeus.

A large Christian community lived in Jerash. A large cathedral was built in the city in the 4th century, the first of at least 14 churches built between the 4th and the 7th-century, many with superb mosaic floors. The supposed sawmill of Gerasa is well described in the Visitors Centre. The use of water power to saw wood or stone is well known in the Roman world: the invention occurred in the 3rd century BC. They converted the rotary movement from the mill into a linear motion using a crankshaft; good examples are known also from Hierapolis and Ephesus.

Umayyad Mosques

Umayyad Houses

Archaeological Museums

The archaeological site of Jerash has two museums in which are displayed archaeological materials and corresponding information about the site and its rich history.

The Jerash Archaeological Museum, which is the older of the two museums, is found on top of the mound known as “Camp Hill” just east of the Cardo and overlooking the Oval Plaza.

The small museum contains a chronological display of artefacts found in and around Jerash from prehistoric to Islamic times.

The museum displays a unique group of small statues of a group identified as the Muses of the Olympic pantheon which were discovered at Jerash in 2016.

The statues, which are Roman in date, were found in a fragmentary condition and have been partially restored.

The museum also contains a well-preserved lead sarcophagus dated to the late 4th to 5th centuries and features Christian and pagan symbolism.

The museum also has several sculptures, altars, and mosaics displayed outside.

The Jerash Visitor Center serves as a more recent archaeological museum and presents the site of Jerash in a thematic approach with a focus on the evolution and development of the city of Jerash over time, as well as the economy, technology, religion, and daily life.

The centre also displays further sculptures discovered in Jerash in 2016, including restored statues of Zeus and Aphrodite, as well as a marble head thought to represent the Roman Empress Julia Domna.

Modern Jerash

Jerash has developed dramatically in the last century with the growing importance of the tourism industry in the city.

Jerash is now the second-most popular tourist attraction in Jordan, closely behind the ruins of Petra.

On the western side of the city, which contained most of the representative buildings, the ruins have been carefully preserved and spared from encroachment, with the modern city sprawling to the east of the river which once divided ancient Jerash into two.

Nestled atop a picturesque hilltop in the Ajloun Governorate, Ajloun Castle (Qal’at Ajloun) stands as a magnificent testament to medieval Islamic military architecture. Far more than just ancient stones, this impressive fortress invites you to step back in time and discover a fascinating chapter of Jordan’s vibrant history. If you’re planning north sites tours in Jordan, Ajloun Castle is an absolute must-see!

Built in 1184 by Izz al-Din Usama, one of Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub’s (Saladin) generals, Ajloun Castle was strategically positioned to defend against Crusader incursions from the west. Its purpose was also to control the local iron mines and monitor the vital trade routes between Syria and Jordan. Imagine the watchful eyes within these walls, diligently guarding the heart of the region!

Over the centuries, the castle saw its share of action. It successfully repelled Crusader attacks, was expanded by the Mamluks, and even withstood the destructive forces of earthquakes, notably in 1837 and 1927. Thankfully, extensive restoration efforts have brought much of its former glory back to life, allowing us to intimately explore its impressive structure today.

As you approach, the sheer scale of Ajloun Castle is breathtaking. Its commanding presence on the landscape truly highlights its strategic importance. Once inside, you can wander through its labyrinthine passages, ascend spiral staircases, and explore its various chambers and towers. Don’t miss the small museum inside that offers a glimpse into the castle’s history and displays artefacts found within its walls.

One of the most rewarding aspects of visiting Ajloun Castle is undoubtedly the panoramic views. From its highest points, you’ll be treated to spectacular vistas of the lush Jordan Valley, the surrounding Ajloun woodlands, and even glimpses of the Israeli-occupied West Bank on a clear day. It’s a photographer’s dream and a perfect moment to reflect on the historical battles and trade that once flowed through this very landscape.

Winter (November through April)

8:00 am – 4:00 pm

Summer

8:00 am – 6:30 pm

April and May

8:00 am – 5:30 pm

The Holy month of Ramadan

8:00 am – 3:30 pm

3 JD (4.25 USD) Includes the museum entrance fees.

Ajloun Castle Entrance Fee included in

Amman to Ajloun Castle around 90 Minutes.

Jerash To Ajloun Castle around 30 Minutes.

Ajloun Castle to Umm Qais around 60 Minutes.

Within Ajloun (Qal’ at Ar-Rabad), a small, but interesting museum the Archaeological Museum (founded in 1993) and it exhibits an extensive, excavated collection of:

pottery.

ceramics.

glass bottles.

stone tools.

metalwork.

coins.

fragments of buildings with intricate drawings and inscriptions.

and other artefacts dating from 1000 BC to 1918 AD.

Anyone visiting Ajloun Castle should visit the museum to have a much better understanding of:

the Great Salah al-Din Al Ayyubi.

the history of the Castle.

and, Also the people who lived in it and around it through thousands of years.

Ajlun Castle is located on the site of an old monastery.

It was renovated as a fort in 1184 by Izz al-Din Usama, a general in the army of Saladin.

The castle controlled traffic along the road connecting Damascus and Egypt.

These enjoyed enough autonomy to ally themselves to the Crusaders and had at one point set up a 100-tent camp next to the Hospitaller castle of Belvoir on the opposite side of the Jordan Valley.

As such, Ajlun Castle is one of the very few Muslim fortresses built by the Ayyubids to protect their realm against Crusader incursions, which could come from Beisan or Belvoir in the west and Karak in the south.

The fortress dominated a wide stretch of the northern Jordan Valley from its location, controlled the three main passages that led to it (Wadi Kufranjah, Wadi Rajeb and Wadi al-Yabis), and protected the communication routes between south Jordan and Syria.

It was built to contain the progress of the Latin Kingdom, which with the Lordship of Oultrejourdain had gained a foothold in Transjordan, and as a retort to the castle of Belvoir a few miles south of the Sea of Galilee.

Another major objective of the fortress was to protect the development and control of the iron mines of Ajlun.

The original castle had four corner towers connected by curtain walls and a double gate.

Arrow slits were incorporated in the thick walls and it was surrounded by a moat averaging 16 meters (about 52 feet) in width and 12–15 meters (about 40–50 feet) in depth.

After Usama’s death, the castle was enlarged in AD 1214–15 by Aibak ibn Abdullah, the Mamluk governor.

He added a new tower in the southeast corner and built the gate.

The castle lost its military importance after the fall of Karak in AD 1187 to the Ayyubids.

In the middle of the 13th century AD, the castle was conceded to Yousef ibn Ayoub, King of Aleppo and Damascus, who restored the northeastern tower and used the castle as an administrative centre.

In 1260 AD, the Mongols destroyed sections of the castle, including its battlements. Soon after the victory of the Mamluks over the Mongols at Ain Jalut, Sultan ad-Dhaher Baibars restored the castle and cleared the fosse.

The castle was used as a storehouse for crops and provisions. When Izz ad-Din Aibak was appointed governor, he renovated the castle as indicated by an inscription found in the castle’s south-western tower.

During the Ottoman period, a contingent of fifty soldiers was set inside the castle.

During the first quarter of the 17th century, Prince Fakhr ad-Din al-Mani II used it during his fight against Ahmad ibn Tarbay. He supplied the castle with a contingent and provided provisions and ammunition.

In 1812, the Swiss traveller Johann Ludwig Burckhardt found the castle inhabited by around forty people.

Two major destructive earthquakes struck the castle in 1837 and 1927.

Recently, the Department of Antiquities of Jordan has sponsored a program of restoration and consolidation of the walls and has rebuilt the bridge over the fosse.

Ajlun Castle is open for tourism.

Many areas of the castle can be explored.

Tourists in Jordan often visit the castle.

Inside there is also a museum exhibition with many interesting artefacts from the various time periods of the region.

Nestled atop a lofty hill overlooking the stunning Jordan Valley, the Sea of Galilee, and the Golan Heights, lies Umm Qais. This ancient site, once known as Gadara, was a prominent Greco-Roman city and a key member of the Decapolis, a league of ten Roman cities in the Middle East. Today, Umm Qais offers a unique blend of archaeological wonders and natural beauty, inviting visitors to step back in time while soaking in panoramic vistas.

Imagine walking through streets once trodden by philosophers, poets, and Roman legions. Umm Qais provides just that experience. As you explore, you’ll encounter the remnants of a glorious past. The wonderfully preserved Roman theatre, carved out of black basalt stone, still boasts impressive acoustics and offers incredible views over the landscape. Nearby, the ruins of a basilica and a charming Byzantine church with its octagonal shape tell tales of early Christian communities. Strolling along the remnants of the main colonnaded street, or decumanus, it’s easy to picture the bustling city life that once thrived here. Don’t forget to visit the small but informative museum housed in the Ottoman-era village houses, which displays artifacts unearthed from the site.

One of the most captivating aspects of Umm Qais is its unparalleled views. From its vantage point, you can gaze across the verdant Jordan Valley to the sparkling waters of the Sea of Galilee (Lake Tiberias) and the distant plains of Syria. It’s a truly spectacular backdrop for exploring history, perfect for photographers and anyone seeking a moment of reflective beauty.

For those planning to explore the rich heritage of northern Jordan, Umm Qais is an absolute must-see and conveniently fits into various north sites tours. Its proximity to other significant historical locations like Jerash and Ajloun makes it an ideal stop on a day trip or an extended cultural itinerary. Many guided north sites tours incorporate Umm Qais, providing comfortable transportation, knowledgeable local guides, and seamless transitions between attractions. This allows you to fully immerse yourself in the experience without worrying about logistics.

Whether you’re a history enthusiast, a nature lover, or simply seeking a tranquil escape with a view, Umm Qais promises an unforgettable visit. Its ancient stones whisper stories of emperors and everyday life, while its expansive horizons remind us of the enduring beauty of this remarkable region. Plan your trip to Umm Qais and discover one of Jordan’s true gems!

Jordan Umm Qais is located 110 km north of Amman.

28 km north of Irbid

around 90 Minute Drive from Amman & 60 Minute From Jerash

Umm Qais or Qays, The Name Meaning (Mother of Qais’)

is a town in northern Jordan umm qais principally known for its proximity to the ruins of the ancient Gadara.

It is the largest city in the Bani Kinanah Department and Irbid Governorate in the extreme northwest of the country, near Jordan’s borders with Israel and Syria.

Today, the site is divided into three main areas: the archaeological site (Gadara), the traditional village (Jordan Umm Qais), and the modern town of Umm Qais.

8:00 am – 4:00 pm

Summer

8:00 am – 6:30 pm

April and May

8:00 am – 5:30 pm

The Holy month of Ramadan

8:00 am – 3:30 pm

Amman to Umm Qais around 90 Minutes.

Umm Qais to Jerash around 60 Minutes.

Umm Qais to Ajloun Castle around 60 Minutes.

Dead Sea to Umm Qais around 2 Hours

Madaba to Umm Qais around 2 Hours

The museum is located above the Acropolis of the ancient city of Gadara.

It Is a house that was built in the late Ottoman period in the 1860s.

The house belongs to the family of Faleh Falah al-Rousan.

It was named Beit al-Rousan (the House of Rousan) in honour of this family. The house is a traditional Arab house type consisting of a spacious central courtyard surrounded by a number of rooms and Diwans of various uses.

It was renovated and adapted as a museum in 1990.

In addition to the archaeological museum on the ground floor, one can enjoy the beautiful views that can be seen from the four sides of the 2nd floor.

Several mountains and cities (from Jordan, Palestine and Syria) can be viewed such as; Mount Tabur, Nazareth, Lake Tiberias, Golan Heights, Yarmouk Valley and Mount Sheikh & More.

After the Rusan family had left their property, the Jordanian architect Ammar Khammash developed the plans for the restoration and as authentic a reconstruction as possible, for which modern conversions and partitions were removed. Some extensions that were necessary for the use as a museum were added following the original architectural style. Work began in 1988/89, financed by various German sources and carried out by the German Evangelical Institute for Classical Studies of the Holy Land (DIE) in collaboration with Ammar Khammash and the German archaeologist Thomas M. Weber.

Umm Qais is located 28 km north of Irbid and 110 km north of Amman.

It expanded from the ruins of ancient Gadara, which are located on a ridge 378 metres (1,240 ft) above sea level, overlooking the Sea of Tiberias, the Golan Heights, and the Yarmouk River gorge.

Strategically central and located close to multiple water sources, Umm Qais has historically attracted a high level of interest.

Antiquity

Gadara was a centre of Greek culture in the region during the Hellenistic and Roman periods.

The name Gadara may have meant “fortifications” or “the fortified city”.

In 63 BCE, Roman general Pompey conquered the region, Gadara was rebuilt and became a member of the semi-autonomous Roman Decapolis.

33 years later Augustus attached it to the Jewish kingdom of his ally, Herod.

After King Herod’s death in 4 BCE, Gadara became part of the Roman province of Syria.

After the Christianisation of the Eastern Roman Empire, Gadara retained its important regional status and became for many years the seat of a Christian bishop.

The oldest archaeological evidence at Umm Qais, some pottery shards found in Garada, extends back to the second half of the third century BC.

The Battle of Yarmouk in 636 a short distance from Gadara, brought the entire region under Arab-Muslim rule.

Around 747 the city was largely destroyed by an earthquake and was abandoned.

in 1596 it appeared in the Ottoman tax registers named as Mkis, situated in the nahiya (subdistrict) of Bani Kinana, part of the Sanjak of Hawran.

It had 21 households and 15 bachelors; all Muslim, in addition to 3 Christian households.

The villagers paid a fixed tax rate of 25% on agricultural products; including wheat, barley, summer crops, fruit trees, goats and bee hives.

The total tax was 8,500 akçe.

In 1838 Um Keis was reported to be in ruins.[10]

Umm Qais boasts an impressive building from the Late Ottoman period, the Ottoman governor’s residence known as Beit Rousan, “Rousan House”.

The ancient classical period city of Gadara, and a member city of the Decapolis(Greek Ten Cities), is one of Jordan’s most dramatic antiquities sites-both for the many substantial ruins of black basalt and white limestone, and for the city’s impressive setting overlooking the north Jordan Valley, the Sea of Galilee The extensive site has scores of standing and still buried monuments covering an area of several hectares.

These include rock-cut tombs with architectural ornaments, facades and Greek inscriptions.

two theatres, one of which is built of black basalt and has a marble sculpture of a goddess seated in the orchestra; a basilica and atrium-shaped courtyard on a semi-artificial terrace, partly restored by the Department of Antiquities and the German Protestant Institute; a street lined on one side with barrel-vaulted shops.

the foundations of the north mausoleum with adjacent traces of the ancient city fortifications; a well preserved underground Roman era mausoleum with an apsidal entrance hall and a crypto-portico; two excavated Byzantine baths complexes; the partly excavated monumental entrance gate to the city; traces of a possible stadium; and various other built structures that have not been excavated.

The late Ottoman village, built from re-used ancient cut stones, is virtually intact on the summit of the site, and some of its houses are being restored and preserved for future use.

History The name Gadara derives from a Semitic term meaning “fortification”, and it is likely that a pre-Hellenistic stronghold secured this stretch of the land route between southern Syria and the north Palestine coastal ports.

The change in the name Gadar/Gadara to Umm Qais in the Middle Ages(from mkes, early Arabic “frontier station”) probably reflects the settlement’s ancient role as a border post.

Gadara first appears in historical records shortly after the conquest of the region by the forces of Alexander the Great in 333 BC.

Alexander’s successors in Egypt, the Ptolemies, refounded Gadara as a military colony along the Yarmouk Valley frontier with their perennial rivals the Seleucids, Alexander’s successors who were based in Antioch, north Syria.

The Roman general Pompey conquered the region of southern Syria in 63BC.

and liberated Gadara and other Hellenistic towns in north Jordan from the grip of the Hasmoneans.

Josephus mentions that due to the damage the city suffered from the siege, Pompey rebuilt it to please Demetrius the Gadarene, one of his favourite freedmen and quite a notable personality in the annals of the late Roman Republic.

It was rumoured in Rome that Demetrius the Gadarene initiated and financed the monumental theatre that was built in Pompey’s honour on the Campus Martius in Rome in 61-54 BC.

After 63 BC, an autonomous Gadara minted its own coins and adopted a new calendar based on the Pompeian era. It was one of the leading cities of the Decapolis (the “ten cities” in Greek), a loose association of at least ten Greco-Roman cities in north Jordan and southern Syria, including Gerasa (modern Jerash), Pella (Tabaqat Fahl), Scythopolis (Beisan), Abila(Qweilbeh) and Philadelphia (Amman).

The Decapolis was a fountainhead of Hellenistic culture in the land of south Syria and north Jordan, and a loyal ally of Rome.

The cities shared common political, cultural, commercial and security interests and, for about 150 years, formed an effective check to expansion by the Nabataeans or the Hasmonaeans of Judaea.

The security which came with the Pax Romana (Roman peace) reinvigorated international trade and boosted the commercial and tax income which the Decapolis cities derived from it. With regional stability completely assured as of the late 1st Century AD, Gadara and the Decapolis entered into their Golden Age of municipal expansion, architectural splendour, economic growth and artistic and cultural vitality.