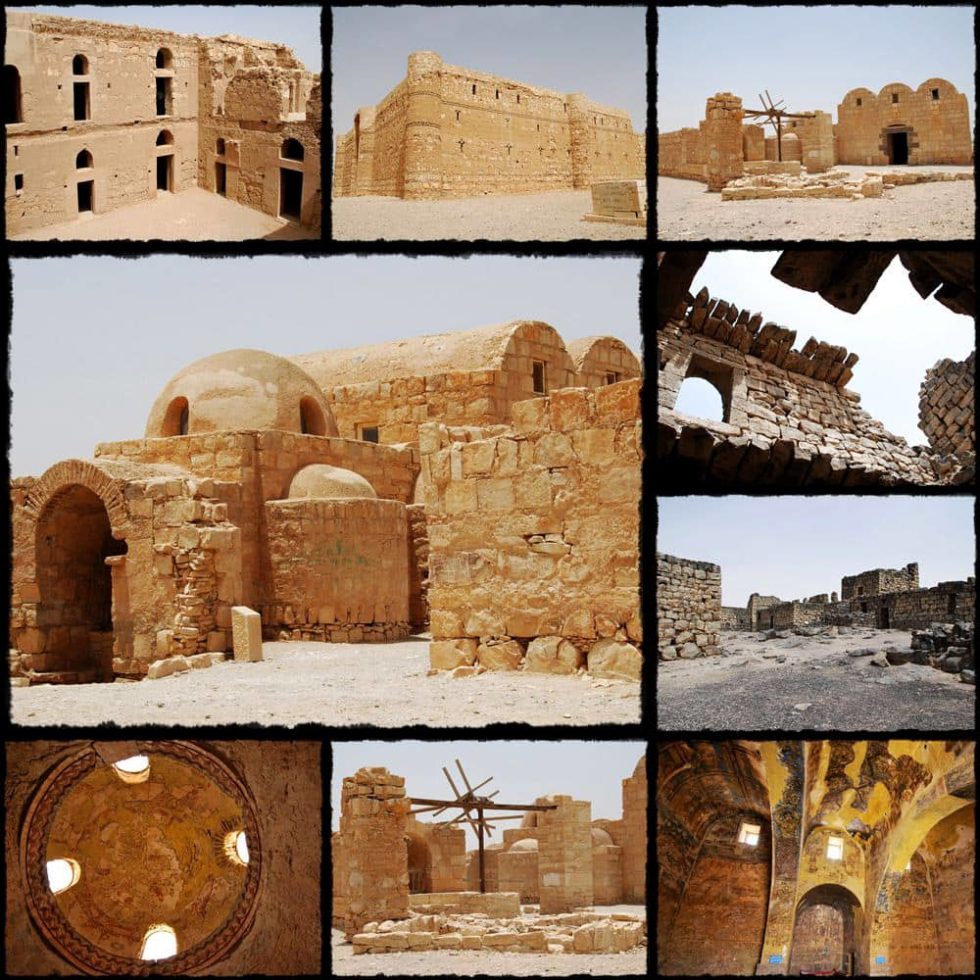

Desert Castles

Desert castles in Jordan, beautiful examples of both early Islamic art and architecture,

stands testament to a fascinating era in the country’s rich history.

Their fine mosaics, frescoes, stone and stucco carvings, and illustrations,

inspired by the best in Persian and Graeco-Roman traditions,

tell countless stories of life as it was during the 8th century.

Qasr Kharana, sometimes Qasr al-Harrana, Qasr al-Kharanah, Kharaneh or Hraneh, is one of the best-known of the desert castles located in present-day eastern Jordan, about 60 kilometres east of Amman and relatively close to the border with Saudi Arabia.

The only entrance gate is centrally located on the southern façade framed by two quarter-round buttresses. Each corner of the 35 m square structure has a three-quarter-round fortification, while semicircular buttresses support the remaining facades at their centre. Narrow openings appear to be arrow slits, but they are too high and actually serve to provide light and ventilation. This proves that al-Kharana wasn’t a military “castle”. First assumptions typified it as a caravanserai, but it was not on any major trade routes and lacked large water sources. It most probably served as a representative place for political meetings between local tribal communities and Umayyad rulers.

located in present-day eastern Jordan, about 60 kilometres (37 mi) east of Amman and relatively close to the border with Saudi Arabia. It is believed to have been built sometime before the early 8th century AD, based on a graffito in one of its upper rooms, despite visible Sassanid influences. A Greek or Byzantine house may have existed on the site. It is one of the earliest examples of Islamic architecture in the region. Its purpose is hard to ascertain with any degree of certainty.

Located in the middle of a vast, treeless plain, this imposing thick-walled structure was the most likely inspiration for the ‘desert castle’ moniker and is arguably the most photogenic of all the desert castles. There is controversy about its function and purpose, but this important Umayyad structure remains an interesting sight for visitors, of the main Azraq–Amman road.

Although it clearly isn’t a castle, Kharana was a vital building for the Umayyads as evidenced by its dramatic size and shape. Despite the fact that it has the appearance of a khan (caravanserai), Kharana wasn’t located on any major trade route, and there appears to be a total absence of structures for water storage. That just leaves the supposition that the building served as a meeting space for Damascus elite and local Bedouin.

Named after the harra (surrounding gravel plains), Kharana lords imposingly over a harsh and barren moonscape that appears inhospitable for human habitation. Inside, however, the internal courtyard provides a calm, protected space that even the wind fails to penetrate.

Despite its castle-like appearance, there is no evidence that the intimidating two-storey building, with what appear to be round, defensive towers and narrow arrow slits, was ever intended as a fort.

Approximately 60 rooms surround the courtyard inside the castle, and they likely served as meeting spaces for visiting delegations. The long rooms on either side of the arched entrance were used as stables, and in the centre of the courtyard was a basin for collecting rainwater. Remarkably, the interior is much smaller than you’d imagine as the walls are deceptively thick.

Climb the broad stairways and you’ll find rooms on the upper storeys with vaulted ceilings. Some carved plaster medallions, set around the top of the walls, are said to indicate Mesopotamian influence.

Also in one of the rooms on the second floor is a few lines of Arabic graffiti, which were crucial in helping to establish the age of the fortress. Above the door in simple black script is an inscription that says ‘Abd Al-Malik the son of Ubayd wrote it on Monday three days from Muharram of the year 92’. Stairs in the southeast and southwest corners lead to the 2nd floor and the roof (closed to visitors).

Very little is known about the origins of Qasr Kharana, although a painted inscription above one of the doors on the upper floor mentions the date AD 710, making it one of the earliest forts of the Islamic era. The presence of stones with Greek inscriptions in the main entrance also suggests it was built on the site of a Roman or Byzantine building, possibly as a private residence.

The entrance to Kharana is through the visitor centre, which has some displays of local history. Public toilets are available. The hospitable owner of the adjacent Bedouin tent, which doubles as the site coffeehouse and souvenir stall, will brew you fresh mint tea and take time to discuss the issues of the day. Your patronage will be much appreciated if the current absence of tourism continues.

Kharana is 16km further west along Hwy 40 from Qusayr Amra. There’s no viable public transport along the highway (although it could be included in a round trip by taxi from Azraq, from JD20) and the castle is only signposted coming from Amman. It’s easier to spot than neighbouring Amra, especially as it’s disappointingly close to a power station.

The building is a square 35 metres (115 ft) on each side, with small projecting corner towers and a projecting rounded entrance on the south side. It is made of rough limestone blocks set in a mud-based mortar. Decorative courses of flat stones run through the facing.

On the inside, the building has 60 rooms on two levels arranged around a central courtyard, with a rainwater pool in the middle. Many of the rooms have small slits for light and ventilation. Some of the rooms are decorated with pilasters, medallions and blind niches finished in plaster.

A graffito in one of the upstairs rooms has allowed the building to be dated to c. 710. However, based on the mixture of styles, some scholars argued that structure was built during the Sasanian occupation of the area in the 620s.

The purpose of the structure remains unclear today. “Castle” is a misnomer as the building’s internal arrangement does not suggest a military use, and slits in its wall could not have been designed for arrowslits. It could have been a caravanserai, or resting place for traders, but lacks the water source such buildings usually had close by and is not on any major trade routes.

Scholarship has suggested that Qasr Kharana might have served a variety of defensive, agricultural and/or commercial agendas similar to other Umayyad palaces in greater Syria. Having a limited water supply it is probable that Qasr Kharana sustained only temporary usage. There are different theories concerning the function of the castle: it may have been a fortress, a meeting place for Bedouins (between themselves or with the Umayyad governor), or used as a caravanserai. The latter is unlikely as it is not directly on a major trade route of the period and lacks the groundwater source that would have been necessary to sustain large herds of camel.

Qasr Kharana combines different regional traditions with the influence of the then-new religion of Islam to create a new style. Syrian building traditions influenced the design of the castle, with Sassanid building techniques applied.

The courtyard

The layout follows Syrian houses, themselves influenced by Byzantine and Roman customs. Several rooms are arranged around a saloon, with the house and another apartment arranged around a central courtyard. Like Sassanid buildings, the castle’s structural system is transverse arches supporting barrel vaults.

Rosette with a tree motif of alternating leaves, early 8th century (Pergamon Museum)

The site made it necessary to modify those building techniques slightly. The arches are not connected to the carrying wall, instead placed on bearing arms. The overall weight of the structure keeps these elements together. Some newer building materials, such as wooden lintels, were used, allowing the building to be more flexible and resist earthquakes.

Islamic concepts of public and private were satisfied through the narrow slits offering views to (and from) the outside, larger windows on the inside and the north terrace separating the two apartments. A room on the south side was set aside for prayer.

The wall slits could not have been used by archers as they are of the wrong height and shape. Instead, they served to control dust and light and took advantage of air pressure differentials to cool the rooms, via the Venturi effect.

The architectural style and the decoration of the building show influences from Syrian, Parthian, and Sasanian traditions. Some scholars argue that the structure was built during the Sasanian occupation of the area in the 620s.

The castle was built in the early Umayyad period by the Umayyad caliph Walid I whose dominance of the region was rising at the time. Qasr Kharana is an important example of early Islamic art and architecture.

In later centuries the castle was abandoned and neglected. It suffered damage from several earthquakes. Alois Musil rediscovered it in 1901, and in the late 1970s, it was restored. During the restoration, some changes were made. A door in the east wall was closed, and some cement and plaster were used that was inconsistent with the existing material.

Stephen Urice wrote his doctoral dissertation on the castle, published as a book, Qasr Kharana in the Transjordan, in 1987 following the restoration.

The castle is just south of Highway 40, an important desert road that links Amman with Azraq, the Saudi Arabian border and remote areas of Eastern Jordan and Iraq. It sits on a slight rise just 15 metres (49 ft) above the surrounding desert. The only other structures in the area are power lines.

Qasr Kharana remains very well preserved. Since it is located just off a major highway and is within a short drive of Amman, it has become one of the most visited desert castles.

The area is fenced off with a visitors’ centre on the southeast corner, where the main entrance to the castle area is located. An unpaved driveway leads from the highway to a dirt parking lot large enough for cars and several buses located just south of the entrance.

The castle is today under the jurisdiction of the Jordanian Ministry of Antiquities. The kingdom’s Ministry of Tourism controls access to the site via the new visitor’s centre, charging an admission fee of JD 2 to the site during daylight hours. A Bedouin merchant is also allowed to sell handcrafts and drinks in the parking lot, as at many other Jordanian tourist sites.

Inside, a large interpretive plaque in Arabic and English is located just inside the main entrance. Visitors are free to explore the entire building, although some of the corridors overlooking the courtyard on the second story do not have guardrails and those who walk there must be careful.

Qusayr ‘Amra or Quseir Amra, lit. “small qasr of ‘Amra”, sometimes also named Qasr Amra, is the best-known of the desert castles located in present-day eastern Jordan. It was built sometime between 723 and 743, by Walid Ibn Yazid, the future Umayyad caliph Walid II, whose dominance of the region was rising at the time.

It is considered one of the most important examples of early Islamic art and architecture.

The building is actually the remnant of a larger complex that included an actual castle, meant as a royal retreat, without any military function, of which only the foundation remains. What stands today is a small country cabin.

It is most notable for the frescoes that remain mainly on the ceilings inside, which depict, among others, a group of rulers, hunting scenes, dancing scenes containing naked women, working craftsmen, the recently discovered “cycle of Jonah”, and, above one bath chamber, the first known representation of heaven on a hemispherical surface, where the mirror-image of the constellations is accompanied by the figures of the zodiac.

This has led to the designation of Qusayr ‘Amra as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The bathhouse is also, along with examples in the other desert castles of Jordan, one of the oldest surviving remains of a hammam in the historic Muslim world.

That status, and its location along Jordan’s major east-west highway, relatively close to Amman, have made it a frequent tourist destination.

Qasr Amra is on the north side of Jordan’s Highway 40, roughly 85 kilometres (53 mi) from Amman and 21 kilometres (13 mi) southwest of Al-Azraq.

It is currently within a large area fenced off in barbed wire.

An unpaved parking lot is located at the southeast corner, just off the road.

A small visitor’s centre collects admission fees. The castle is located in the west of the enclosed area, below a small rise.

Traces of stone walls used to enclose the site suggest it was part of a 25-hectare (62-acre) complex; there are remains of a castle that could have temporarily housed a garrison of soldiers.

Just to the southeast of the building is a well 40 metres (130 ft) deep, and traces of the animal-driven lifting mechanism and a dam have been found as well.

The architecture of the reception-hall-cum-bathhouse is identical to that of Hammam al-Sarah, also in Jordan, except the latter was erected using finely-cut limestone ashlars (based on the Late Roman architectural tradition), while Amra’s bath was erected using rough masonry held together by gypsum-lime mortar (based on the Sasanian architectural tradition).

It is a low building made from limestone and basalt.

The northern block, two stories high, features a triple-vaulted ceiling over the main entrance on the east facade. The western wings feature smaller vaults or domes.

One of the six kings depicted is King Roderick of Spain, whose short reign (710-712) was taken to indicate the date of the image, and possibly the building, to around 710. Therefore, for a long time, researchers believed that sitting caliph Walid I was the builder and primary user of Qasr Amra, until doubts arose, making specialists believe that one of two princes who later became caliph themselves, Walid or Yazid, were the more likely candidates for that role.

The discovery of an inscription during work in 2012 has allowed for the dating of the structure to the two decades between 723 and 743, when it was commissioned by Walid Ibn Yazid, a crown prince under caliph Hisham and his successor during a short reign as caliph in 743–744.

Both princes spent long periods of time away from Damascus, the Umayyad capital, before assuming the throne. Walid was known to indulge in the sort of sybaritic activities depicted on the frescoes, particularly sitting on the edge of pools listening to music or poetry. He was once entertained by performers dressed as stars and constellations, suggesting a connection to the sky painting in the caldarium. Yazid’s mother was a Persian princess, suggesting a familiarity with that culture, and he too was known for similar pleasure-seeking.

A key consideration in the placement of the desert castles centred on access and proximity to the ancient routes running north from Arabia to Syria. A major route ran from the Arabian city of Tayma via Wadi Sirhan toward the plain of Balqa in Jordan and accounts for the location of Qusayr Amra and other similar fortifications such as Qasr Al-Kharanah and Qasr al-tuba.

The abandoned structure was re-discovered by Alois Musil in 1898, with the frescoes made famous in drawings by the Austrian artist Alphons Leopold Mielich for Musil’s book. In the late 1970s, a Spanish team restored the frescoes. The castle was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985 under criteria(“masterpiece of human creative genius”, “unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition” and “an outstanding example of a type of building, architectural or technological ensemble or landscape which illustrates a significant stage in human history”).

The Painting of the Six Kings is a fresco found on the wall of Qasr Amra, a desert castle of the Umayyad Caliphate located in modern-day Jordan. It depicts six rulers standing in two rows of three.

Four of the six have inscriptions in Arabic and Greek identifying them as the Byzantine emperor, King Roderic of Hispania, the Sasanian emperor, and the Negus of Aksum.

The painting, now substantially damaged, is thought to be from between 710 and 750,

commissioned by the Umayyad caliph or someone in his family. It is one of the most famous frescoes in the Qasr Amra complex.

The painting is located in Qasr Amra (also transcribed “Quseir Amra”, literally “little palace of Amra”), an Umayyad desert structure and a UNESCO World Heritage Site about 85 kilometres (53 mi) east of Amman and 21 kilometres (13 mi) southwest of the Azraq Oasis in modern-day Jordan.

The complex has several frescoes painted on its walls.

The remoteness and size of the structure suggest that it served as a desert retreat for Umayyad rulers at the time.

The painting is on the southern end of the west portion of the main wall.

Along with other works in the complex, it was cleaned and preserved in the 1970s by a team from the National Archaeological Museum of Spain.

Historian Elizabeth Drayson estimated the earliest possible date for the painting to be 710, the year of the accession of Roderic – one of the kings portrayed in the painting – and the latest to be 750, the year of the Abbasid Revolution that overthrew the Umayyads.

The artist who painted the fresco is unknown. The patron who commissioned the building, including the painting, was likely one of the caliphs al-Walid I (reigned 705–715), al-Walid II (r. 743–744) or Yazid III (r. 744).[10] It might have been commissioned after the patron became caliph, or before when the patron was a member of the caliph’s family and held the position of governor or heir.

The complex, long familiar to local nomads, was first visited by a Westerner in 1898, by the Czech scholar Alois Musil.[8] He first arrived in the complex and saw the paintings on 8 June that year, guided by a group of bedouins.

Musil and his companion, Austrian artist Alphons Leopold Mielich, tried to remove the painting from the site, causing permanent damage.

A fragment of the painting, containing labels and partial crowns of two of the figures, is now in the Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin.

Musil’s 1907 publication Kusejr ‘Amra included a tracing made by Mielich on the spot, Musil’s interpretative copy made on the spot, Mielich’s later reproduction, and Mielich’s written description of the painting.

This publication included their observations made before much of the damage to the painting was done.

The painting is badly damaged, partly due to the efforts by Alois Musil to remove it.

Large portions of the figures and their garments are not clearly visible. There are six rulers, or kings, standing facing the viewer in two rows of three.

Each king stretches out both hands with palms turned upwards. Inscriptions in Greek and Arabic above four of the figures, written in white letters on a blue background, identify them as:

– Kaisar/Qaysar (“Caesar”), the Byzantine emperor, face not visible, wearing imperial robes and tiara.

– Rodorikos/Ludhriq, Roderic, the Visigothic king of Hispania, barely visible, except for the tip of his helmet and robes.

– Khosroes/Kisra, the Sasanian emperor, appearing young with curly hair, wearing a crown, a cloak, and shoes.

– Najashi, the Negus of the Kingdom of Aksum, in a light garment with a red stole.

The labels were already fragile when Musil found it, and many of the labels were lost when he and Mielich tried to clean the painting and remove it from the site.[13] However, Musil’s 1907 publication provided his reproduction of the labels before the damage.[17] Apart from the four rulers, no identification remains visible for the other two rulers. Possible identities speculated for them include the emperor of China, a Turkic leader, and an Indian ruler.

Alongside the painting of the six kings, on the same wall, is a painting of a woman with the Greek word ΝΙΚΗ Nikē “Victory” above her.

Opposite the painting, towards which the six rulers are gesturing, is a painting of a man seated on a throne. Above this man is an inscription containing a blessing on a person whose name is now invisible.

The intent and meaning of the painting are unclear and disputed by scholars. The highly diverse interpretations of the painting are partly due to the loss of information from the damage.

According to Islamic art consultant Patricia Baker, the Greek word for “victory” appearing nearby suggests that the image was meant to suggest the caliph’s supremacy over his enemies.[10] Betsy Williams of the Metropolitan Museum of Art suggested that the six figures are depicted in supplication, presumably towards the caliph who would be seated in the hall.[4] Other scholars, including Arabic epigraphist Max van Berchem and architectural historian K. A. C. Creswell, argued that the six rulers are a representation of the defeated enemies of Islam.[20] Iranologist and archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld argued that the painting is an Umayyad copy or version of the Sassanian “Kings of the Earth” located at Kermanshah, as recorded by Yaqut al-Hamawi in his work Mu’jam al-Buldan (Dictionary of Countries).

Art historian Oleg Grabar interpreted the painting as an attempt to convey the idea that the Umayyad dynasty was the descendant and heir of the dynasties it had defeated.

The main entry vault has scenes of hunting, fruit and wine consumption, and naked women. Some of the animals shown are not abundant in the region but were more commonly found in Persia, suggesting some influence from that area. One surface depicts the construction of the building. Near the base of one wall a haloed king is shown on a throne. An adjoining section, now in Berlin’s Museum of Islamic Art, shows attendants as well as a boat in waters abundant with fish and fowl

An image known as the “six kings” depicts the Umayyad caliph and the rulers of realms near and far.

Based on details and inscriptions in the image, four of the depicted kings are identified as the Byzantine Emperor, the Visigothic king Roderic, the Sassanid Persian Shah, and the Negus of Ethiopia.

The last one was for a long time unidentified, speculated to be the Turkish, Chinese, or Indian ruler, and now known to represent the emperor of China.

Its intent was unclear. The Greek word ΝΙΚΗ Nike, meaning victory, was discovered nearby, suggesting that the “six kings” image was meant to suggest the caliph’s supremacy over his enemies.

Another possible interpretation is that the six figures are depicted in supplication, presumably towards the Caliph who would be seated in the hall.

The frescoes in all rooms but the caldarium reflect the advice of contemporary Arab physicians. They believed that baths drained the spirits of the bathers, and that to revive “the three vital principles in the body, the animal, the spiritual and the natural,” the bath’s walls should be covered with pictures of activities like hunting, of lovers, and of gardens and palm trees.

The apodyterium, or changing room, is decorated with scenes of animals engaging in human activities, particularly performing music. One ambiguous image has an angel gazing down on a shrouded human form. It has often been thought to be a death scene, but some other interpretations have suggested the shroud covers a pair of lovers.

Three blackened faces on the ceiling have been thought to represent the stages of life. Christians in the area believe the middle figure is Jesus Christ.

On the walls and ceiling of the tepidarium, or warm bath, are scenes of plants and trees similar to those in the mosaic at the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. They are interspersed with naked females in various poses, some bathing a child.

The caldarium or hot bath’s hemispheric dome has a representation of the heavens in which the zodiac is depicted, among 35 separate identifiable constellations. It is believed to be the earliest image of the night sky painted on anything other than a flat surface. The radii emerge not from the dome’s centre but, accurately, from the north celestial pole. The angle of the zodiac is depicted accurately as well. The only error discernible in the surviving artwork is the counterclockwise order of the stars, which suggests the image was copied from one on a flat surface.

Qasr al-Azraq (Arabic: “Blue Fortress”) is a large fortress located in present-day eastern Jordan. It is one of the desert castles, located on the outskirts of present-day Azraq, roughly 100 km (62 mi) east of Amman.

Its strategic value came from the nearby oasis, the only water source in a vast desert region. The name of the fortress and the associated town came from these. The settlement was known in antiquity as Basie and the Romans were the first to make military use of the site, and later an early mosque was built in the middle. It did not assume its present form until an extensive renovation and expansion by the Ayyubids in the 13th century, using locally quarried basalt which makes the castle darker than most other buildings in the area.

Later, it would be used by the Ottoman armies during that empire’s hegemony over the region. During the Arab Revolt, T.E. Lawrence based his operations here in 1917–18, an experience he wrote about in his book Seven Pillars of Wisdom. The connection to “Lawrence of Arabia” has been one of the castle’s major draws for tourists.

The castle is constructed of the local black basalt and is a square structure with 80 metre long walls encircling a large central courtyard. In the middle of the courtyard is a small mosque that may date from Umayyad times. At each corner of the outer wall, there is an oblong tower. The main entrance is composed of a single massive hinged slab of granite, which leads to a vestibule where one can see carved into the pavement the remains of a Roman board game.

Although very heavy — 1 ton for each of the leaves of the main gate, 3 tons for single the other — these stone doors can quite easily be moved, thanks to palm tree oil. The unusual choice of stone can be explained by the fact that there is no close source of wood, apart from palm tree wood, which is very soft and unsuitable for building.

The strategic significance of the castle is that it lies in the middle of the Azraq oasis, the only permanent source of fresh water in approximately 12,000 square kilometres (4,600 sq mi) of the desert. Several civilizations are known to have occupied the site for its strategic value in this remote and arid desert area.

The area was inhabited by the Nabataean people and around 200 CE fell under the control of the Romans. The Romans built a stone structure using the local basalt stone that formed a basis for later constructions on the site, a structure that was equally used by the Byzantine and Umayyad empires.

Qasr al-Azraq underwent its final major stage of building in 1237 CE, when ‘Izz ad-Din Aybak, an emir of the Ayyubids, redesigned and fortified it. The fortress in its present form dates to this period.

In the 16th century, the Ottoman Turks stationed a garrison there, and T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) made the fortress his desert headquarters during the winter of 1917, during the Great Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire. His office was in the chamber above the entrance gatehouse.

It had an additional advantage in modern warfare: the flat nearby desert was an ideal place to build an airfield.

According to Lawrence, “Azrak lay favourably for us, and the old fort would be convenient headquarters if we made it habitable, no matter how severe the winter. So I established myself in its southern gate-tower and set my six Haurani boys…to cover with brushwood, palm-branches, and clay the ancient split stone rafters, which stood open to the sky.” Ali ibn el Hussein “took up his quarters in the south-east corner tower, and made that roof tight.” The postern gate was shut each night, “The door was a poised lab of dressed basalt, a foot thick, turning on pivots of itself, socketed into threshold and lintel. It took a great effort to start swinging, and at the end went shut with a clang and crash which made tremble the west wall of the old castle.”

Lawrence wrote of their first night, “…when there rose a strange, long wailing round the towers outside. Then the cries came again and again and again, rising slowly in power, till they sobbed round the walls in deep waves to die away choked and miserable. Lawrence was told, “…the dogs of the Beni Hillal, the mythical builders of the fort, quested the six towers each night for their dead masters…their ghost-watch kept our ward more closely than arms could have done.”

Qasr al-Azraq is often included on day trips from Amman to the desert castles, along with Qasr Kharana and Qasr Amra, both east of the capital and reached via Highway 40. Admission is JD 2. Visitors can explore most of the castle, both upstairs and downstairs, except for some sections closed off while the rock is shored up.